An Unexpected Hero

River City Rising

Although I have, on many occasions, visited the riverfront park named after him, I am a bit embarrassed to admit it was not until recently that I researched Mr. Tom Lee. Better late than never and rather coincidentally (or not) history would in a way repeat itself shortly after I’d finished my research.

To quickly summarize his heroic story, Tom Lee, an African American man who could not swim, risked his life to save passengers aboard the M.E. Norman, a steamboat that capsized in the Mississippi river. As the only witness to the tragic incident he rescued 32 people using his small skiff, making five trips from the steamboat to shore. Lee moved swiftly, led by his heart, rather than being held back by any second-guessing that may have been going on in his head.

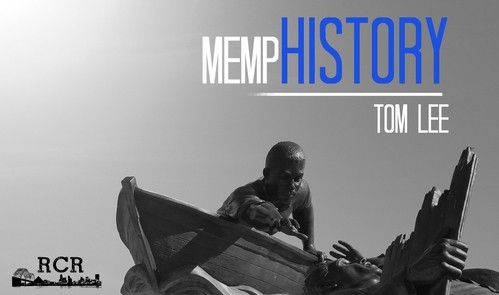

The passengers aboard the M.E. Norman were engineers and their family members on a sightseeing excursion provided by the Army Corps of Engineers. Lee was a poor man who made his living as a fisherman and farm hand. That afternoon in 1925, lives that may otherwise have never intertwined became lives forever joined by one man’s act of selflessness. It is an act that has been aptly depicted by artist David Alan Clark’s bronze sculpture, which stands in the park bearing Lee’s name: Lee leans over the edge of his boat with outstretched hand to help a man desperately reaching up towards him.

To quickly summarize his heroic story, Tom Lee, an African American man who could not swim, risked his life to save passengers aboard the M.E. Norman, a steamboat that capsized in the Mississippi river. As the only witness to the tragic incident he rescued 32 people using his small skiff, making five trips from the steamboat to shore. Lee moved swiftly, led by his heart, rather than being held back by any second-guessing that may have been going on in his head.

The passengers aboard the M.E. Norman were engineers and their family members on a sightseeing excursion provided by the Army Corps of Engineers. Lee was a poor man who made his living as a fisherman and farm hand. That afternoon in 1925, lives that may otherwise have never intertwined became lives forever joined by one man’s act of selflessness. It is an act that has been aptly depicted by artist David Alan Clark’s bronze sculpture, which stands in the park bearing Lee’s name: Lee leans over the edge of his boat with outstretched hand to help a man desperately reaching up towards him.

Such acts of selflessness continue today in Memphis and, still, between the unlikeliest of people. Several weeks ago Tyteaddis Johnson was honored by Shelby County Mayor Mark Luttrell for saving the life of Ms. Margaret Dobbs, who had become trapped in her car after a horrific crash on Airways Boulevard. Mr. Johnson, a Shelby County jail inmate who was part of a work crew cutting grass nearby, knowingly violated the rules of his incarceration when he rushed to Dobbs’ aid. Dobbs was quoted by reporter Darcy Thomas as saying, “He risked everything to go and get and cut me out. He didn't think about his own well being or getting in trouble. He thought about helping me."

Two accidents occurring 89 years apart give us the chance to see the very best in humanity displayed by men who chose to put the lives of others before their own. Two men ignored risk, skin color and status to do what they instinctively knew to be right. As someone shared with me recently, “Sometimes it’s the person we least expect or respect who is revealed to be the hero.”

Two accidents occurring 89 years apart give us the chance to see the very best in humanity displayed by men who chose to put the lives of others before their own. Two men ignored risk, skin color and status to do what they instinctively knew to be right. As someone shared with me recently, “Sometimes it’s the person we least expect or respect who is revealed to be the hero.”